The Monroe Doctrine, first outlined in a speech to Congress in 1823, had President James Monroe warning European powers to not attempt further colonization, military intervention or other interference in the Western Hemisphere, stating that the United States would view any such interference as a potentially hostile act. Over the centuries, the Monroe Doctrine policy has become a cornerstone of U.S. diplomatic and military policies.

By the early 1820s, many Latin American countries had won their independence from Spain or Portugal, with the U.S. government recognizing the new republics of Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia and Mexico in 1822.

Yet both Britain and the United States worried that the powers of continental Europe would make future attempts to restore colonial regimes in the region. Russia had also inspired concerns of imperialism, with Czar Alexander I claiming sovereignty over territory in the Pacific Northwest and banning foreign ships from approaching that coast in 1821.

Though Monroe had initially supported the idea of a joint U.S.-British resolution against future colonization in Latin America, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams argued that joining forces with the British could limit future U.S. opportunities for expansion, and that Britain might well have imperialist ambitions of its own.

Adams convinced Monroe to make a unilateral statement of U.S. policy that would set an independent course for the young nation and claim a new role as protector of the Western Hemisphere.

James MonroeWATCH: James Monroe

During the president’s customary message to Congress on December 2, 1823, Monroe expressed the basic tenets of what would later become known as the Monroe Doctrine.

According to Monroe’s message (drafted largely by Adams), the Old World and the New World were fundamentally different, and should be two different spheres of influence. The United States, for its part, would not interfere in the political affairs of Europe, or with existing European colonies in the Western Hemisphere.

“The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for colonization by any European powers,” Monroe continued. Any attempt by a European power to exert its influence in the Western Hemisphere would, from then on, be seen by the United States as a threat to its security.

In declaring separate spheres of influence and a policy of non-intervention in the foreign affairs of Europe, the Monroe Doctrine drew on past statements of American diplomatic ideals, including George Washington’s Farewell Address in 1796, and James Madison’s declaration of war with Britain in 1812.

At the time Monroe delivered his message to Congress, the United States was still a relatively minor player on the world stage. It clearly did not have the military or naval power to back up its assertion of unilateral control over the Western Hemisphere, and Monroe’s bold policy statement was largely ignored outside U.S. borders.

In 1833, the United States did not invoke the Monroe Doctrine to oppose British occupation of the Falkland Islands; it also declined to act when Britain and France imposed a naval blockade against Argentina in 1845.

But as the nation’s economic and military strength grew, it began backing up Monroe’s words with actions. When the Civil War drew to a close, the U.S. government supplied military and diplomatic support to Benito Juárez in Mexico, enabling his forces to overthrow the regime of Emperor Maximilian, who had been placed on the throne by the French government, in 1867.

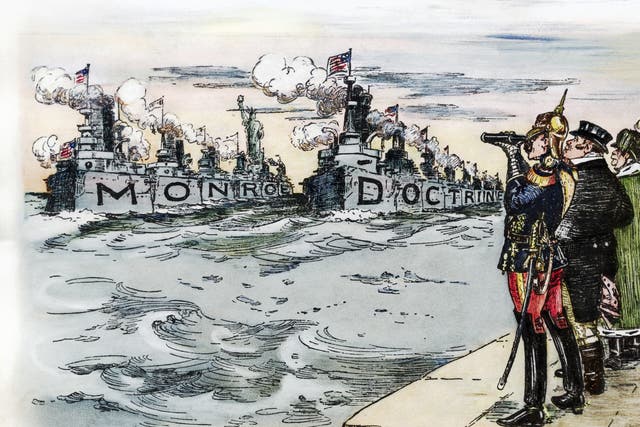

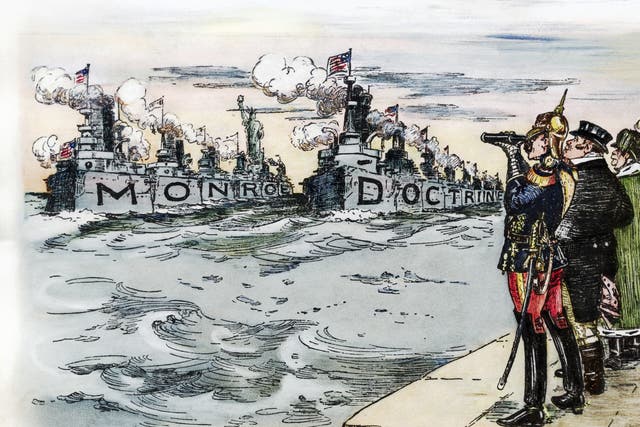

From 1870 onward, as the United States emerged as a major world power, the Monroe Doctrine would be used to justify a long series of U.S. interventions in Latin America. This was especially true after 1904, when President Theodore Roosevelt claimed the U.S. government’s right to intervene to stop European creditors who were threatening armed intervention in order to collect debts in Latin American countries.

But his claim went further than that. “Chronic wrongdoing. may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation,” Roosevelt announced in his annual message to Congress that year. “In the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.”

Known as the “Roosevelt Corollary” or the “Big Stick” policy, Roosevelt’s expansive interpretation was soon used to justify military interventions in Central America and the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Haiti and Cuba.

Some later policymakers tried to soften this aggressive interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who introduced a Good Neighbor policy to replace the Big Stick.

But though treaties signed during and after World War II reflected a policy of greater cooperation between North and South American countries, including the Organization for American States (OAS), the United States continued to use the Monroe Doctrine to justify its interference in the affairs of its southern neighbors.

During the Cold War era, President John F. Kennedy invoked the Monroe Doctrine during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when he ordered a naval and air quarantine of Cuba after the Soviet Union began building missile-launching sites there. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan similarly used the 1823 policy principle to justify U.S. intervention in El Salvador and Nicaragua, while his successor, George H.W. Bush, similarly sanctioned a U.S. invasion of Panama to oust Manuel Noriega.

With the end of the Cold War and the dawn of the 21st century, the United States reduced its military involvements in Latin America, while continuing to assert a powerful influence in the affairs of the region.

At the same time, socialist leaders in Latin America, such as Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela, have earned support from their citizens by resisting what they view as U.S. imperialism, underscoring the complicated legacy of the Monroe Doctrine and its defining influence on U.S. foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere.

Monroe Doctrine, 1823. U.S. State Department: Office of the Historian.

“Before Venezuela, US had long involvement in Latin America.” Associated Press, January 25, 2019.

“The Economist Explains: What is the Monroe Doctrine?” The Economist, February 12, 2019.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, 1904. OurDocuments.gov.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen and Christian Zapata.